Names are a system for storing and retrieving information. When we use the wrong name, everything we think we know about the object of the name is incorrect.

My key points here are:

- Identification is never about recognizing ONE species; it’s about considering and excluding all other plausible candidates.

- Identifications are not definitive knowledge. They are hypothetical.

When is an identification reliable?

When we try to identify something, we usually intend to find a depiction as close as possible to our specimen.

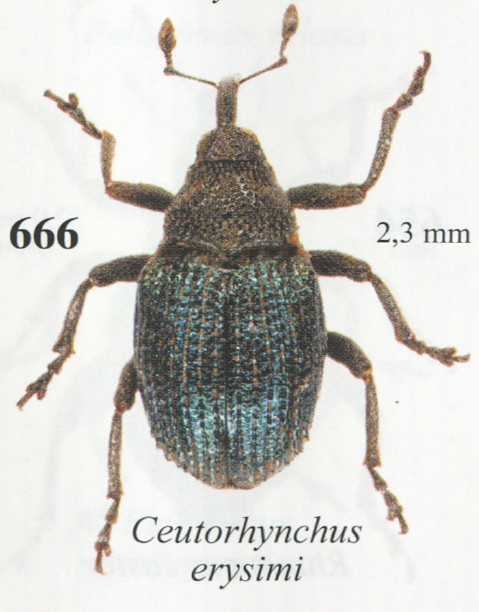

Imagine you find this weevil:

(Image: skitterbug, CC-BY)

As the specimen seems to be very unusual (blue metallic color, suspicious shape), it would be reasonable to look if an image of such a weevil can be found with a name somewhere. You might find something like this:

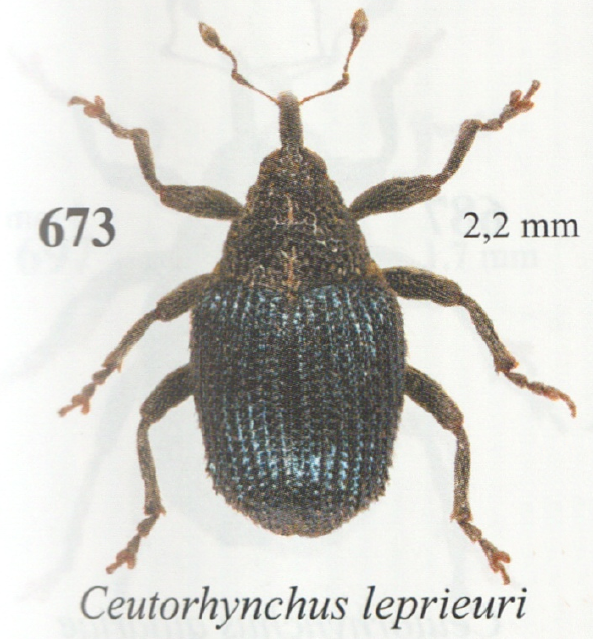

(Image: Rheinheimer & Hassler 2013: Die Rüsselkäfer Baden-Württembergs)

The novice taxonomist might now be satisfied with themselves, write down the name Ceutorhynchus erysimi, and proceed to indulge in the absorption of everything that has been written about its biology. Just fascinating! A price well earned for all the hard work!

But wait:

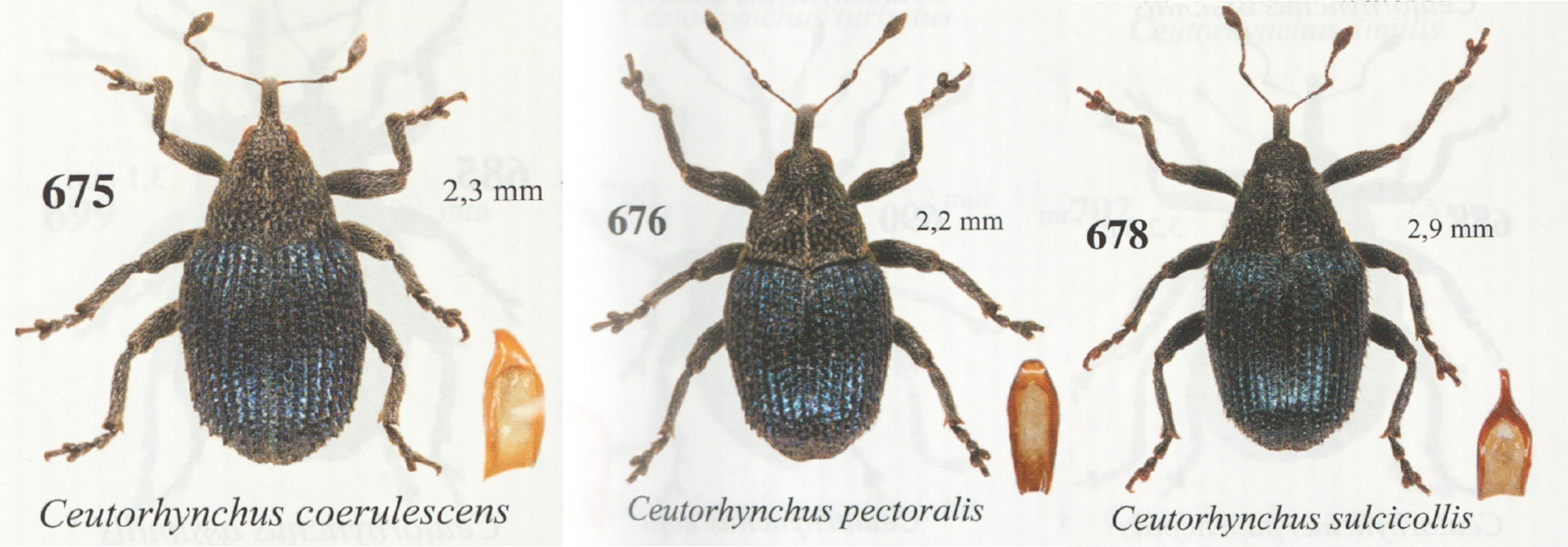

(Image: Rheinheimer & Hassler 2013: Die Rüsselkäfer Baden-Württembergs)

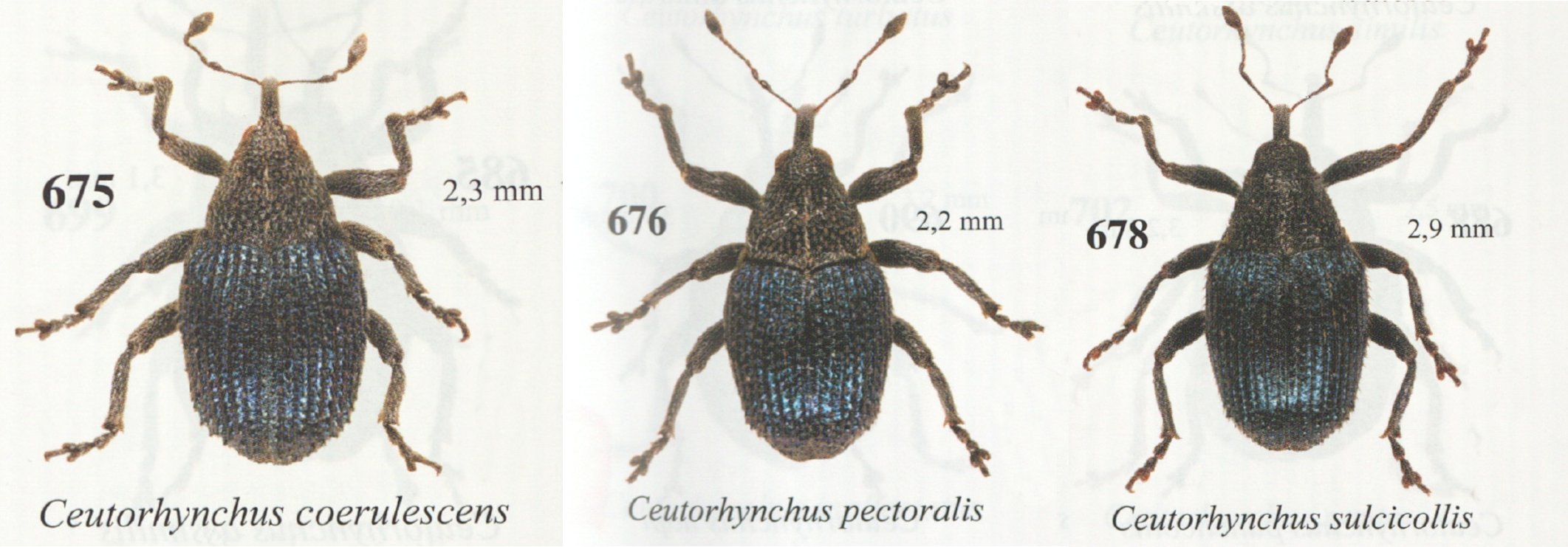

Actually there are quite a lot of extremely similar species of blue Ceutorhynchus. Here are three more, just as an example:

(Image: Rheinheimer & Hassler 2013: Die Rüsselkäfer Baden-Württembergs, modified)

While those species look very similar, they differ in important aspects, such as their choice of host plants. Some are pests of agricultural crops, others are rare and endangered.

It’s never enough to find a species that resembles your specimen:

A reliable identification requires ruling out all other possibilities.

Any species could have one or more lookalikes, even if it looks strikingly different from anything you’ve ever seen. It is surprising how often people fall for this. Sometimes I even notice this tendency in myself!

Do we have to compare all existing species with each other?

This brings us to an important question: How can we rule out the existence of look-alike species? We cannot know every existing species!

The two primary tools at our disposal are:

- identification keys

- checklists (or catalogs)

Identification keys guide us through the process of comparing all the species with each other. They simplify the process, as they use diagnostic characters to exclude large numbers of candidates early on. The blue Ceutorhynchus from the example above can be divided into species with teethed claws, and those with simple claws. Characters like this are incredibly useful but usually not visible in images, not even excellent macro photographs. This is one reason why entomologists have to collect and mount specimens.

Example: Key to the palearctic species of the genus Tychius

Checklists are lists of species. Most importantly they contain information on synonymy between names, but also on distribution and sometimes additional information, such as host plants or images. Checklists are often more recent than keys, as they are easier to update, and sometimes they are maintained as online databases. Just as keys, checklists can have a primarily geographical (“The Beetles of Germany”) or taxonomical (“Catalogue of Ceutorhynchinae of the World”) focus. Ideally, a key should be compared with a checklist to ensure it is not missing important species (recent introductions of new species into an area, newly described species).

Example: Cooperative Catalogue of Palearctic Coleoptera Curculionoidea, Second Edition

The sheer number of described insect species presents a significant challenge in entomology. To date, there is not even a list containing every weevil species. Keys and checklists organize and condense the available knowledge to make it accessible. You could think of them as an index of biodiversity.

Be aware that online databases such as GBIF are extremely useful and I encourage everyone to use them, but they are less reliable than a good (!) checklist. Authors of checklists have often made significant efforts to verify information, such as examining collections to ensure that specimens are correctly identified.

Species identifications are hypotheses

In principle, a species identification is the claim that a specimen belongs to the same species concept as a given type specimen. The type specimen bears the species name, it is the connection between a name and a real object.

From a philosophical point of view, knowledge is never 100% certain. Scientific knowledge is produced as a hypothesis:

- A hypothesis is preliminary, it is not absolute knowledge

- A hypothesis can be tested

- A hypothesis can be falsified through testing

If we find a weevil, we can propose the hypothesis “the weevil in my hands is identical with the type specimen of Ceutorhynchus erysimi”, thus assigning that name to our specimen as an identification.

An identification can be made using various lines of evidence. Every trait observed in the specimen, which matches traits of a known species, makes it more likely that the identification is correct. But the presence of unobserved differing characters can never be excluded with certainty!

The identification can be tested and falsified, but it cannot be proven.

In an image, the number of observable characters is very limited. In such a case, supporting information such as the locality or the host plant is often included in the decision (“C. erysimi is the only species with blue elytra which has been found in this area”). Experience can help to learn if a trait is reliable or not.

(Image: Rheinheimer & Hassler 2013: Die Rüsselkäfer Baden-Württembergs, modified)

An example to illustrate why identifications are always preliminary

Not only is our identification hypothetical, but so is the very concept of Ceutorhynchus erysimi itself. In case someone else discovers there are two species behind the concept, our identification needs to be re-examined. This is not common, but probably more common than you think.

An example: For a long time, only two species of Colydium were known from Europe: C. elongatum and C. filiforme. In 2024, a third species, C. noblecourti, was described (Parmain et al., 2024). It has always been present in this well-surveyed area but is less common than the other two. Its characteristics have just been overlooked for centuries!

The new species is supported not only by morphological characters but also by genetics. This is a wonderful example, illuminating how genetic data and morphological data can complement each other.

Using the older keys, one would get to C. elongatum when trying to identify a specimen of the new species. After I learned about the new species, I checked the collection at the Senckenberg Naturmuseum in Frankfurt. The identification labels on the pins of the specimens there told me that the entire material had already been checked by the author of an earlier revision of Colydium (Węgrzynowicz, 1999), who did not notice the presence of a third species.

The new key by Parmain et al., 2024 allowed me to identify the third species amongst the material. It is surprisingly easy to identify with the key, but without it I would have never spotted the difference between the two known species and the third one. It is understandable that Węgrzynowicz overlooked the undescribed species, as the distinguishing characters are easy to dismiss as intraspecific variation without the genetic evidence showing that they belong to a distinct lineage.

The genetic analysis by Parmain et al., 2024 revealed morphological characters that distinguish the species. As a result, others can now identify the same species based on external features alone, without needing genetic data. It’s a remarkable example of how genetics can pave the way for easier, morphology-based identification. Wonderful!

Diagnostic characters become apparent only after examining large numbers of specimens. Identification keys are the result of intensive comparative work by their authors, who in this case even verified that the morphological characters correspond to genetic lineages. Keys allow others to make reliable identifications without needing to repeat the same exhaustive comparisons.

Therefore, whenever someone wrote about Colydium elongatum before 2024, the identification actually refers to “C. elongatum OR C. noblecourti”. Entries from before 2024 in literature or databases cannot be verified unless they point to a specimen. Some studies indicate a collection where voucher specimens are deposited.

If you identify a blue Ceutorhynchus without knowing about the existence of more than one blue Ceutorhynchus, you make the same mistake as the whole entomological community before the description of C. noblecourti in 2024! The ability to identify is hampered both by limited knowledge of the scientific community and by your personal knowledge. It is extremely difficult to observe characters without the guidance of literature. If you keep voucher specimens, your identifications can be re-examined in the light of new information.

Miracles

People who have identified a lot of specimens seem to develop supernatural perception. After going through keys for hours, after verifying the results with reference specimens, it can be quite frustrating to learn that an expert, when asked if your identification is correct, seems to be able to judge it without even looking through the microscope!

The explanation for this strange phenomenon is that they have seen enough specimens that they recognize them intuitively, just as we can identify the face of a close friend among millions of other faces. Would you be able to describe the characteristics of that face using words? Probably not!

We sacrifice a type specimen to the deity of taxonomy: grant us luck and resilience whenever life feels like navigating a cryptic key with dubious illustrations and erratic vocabulary. May clear characters and concise language help us to make the right decisions along the way. May the results of our identifications spark joy in our hearts while adding new species to regional faunistic catalogues. Amen.

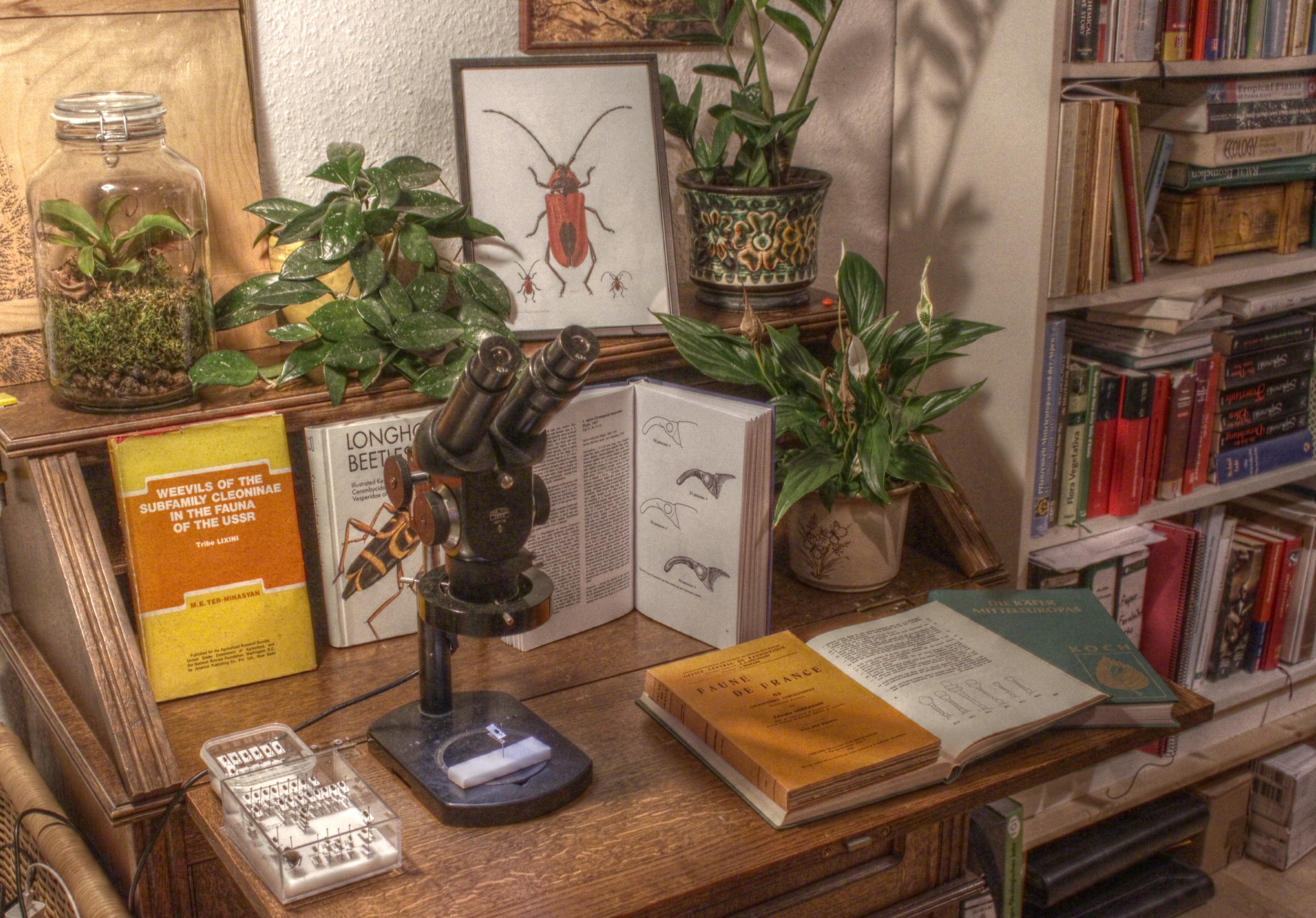

Image composed from three exposures with varying brightness (HDR), processed using the tone mapping filter by Mantiuk et al. (2006) in Luminance HDR.

This text is loosely based on a talk I held at the 75 year anniversary congress of the DJN - Jugendbund für Naturbeobachtung